- Climate Action and Participatory Democracy

- Governance issues (Accountability and Transparency)

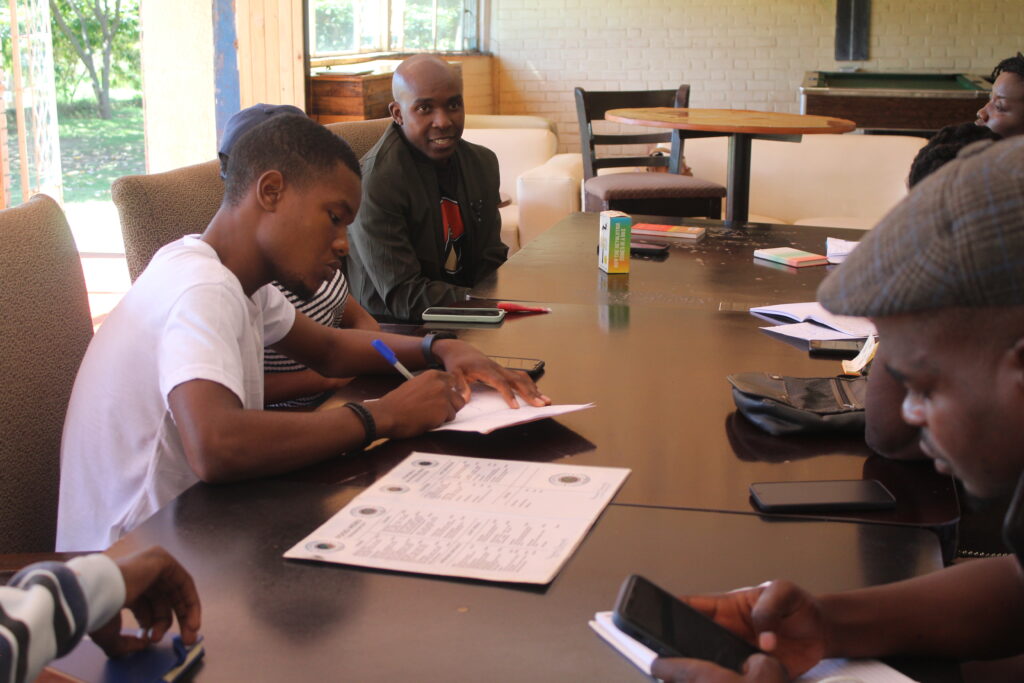

Date: Saturday, May 10, 2025

Location: Harare, Zimbabwe

Participants: ZINASU National Executive Council (NEC)

Introduction

This report encapsulates the vital discussions and insights gained from a comprehensive training program held on May 10, 2025, in Harare, Zimbabwe, for the National Executive Council (NEC) of the Zimbabwe National Students Union (ZINASU). The training focused on two critical, interconnected themes: “Climate Action and Participatory Democracy” and “Governance Issues on Accountability and Transparency.” Facilitated by Natalie Gwatirisa the director at Global Impact Initiative and Ntandoyenkosi Dumani the programs officer at Friedrich Ebert Stiftung- Zimbabwe, the sessions aimed to equip ZINASU NEC members with the knowledge, tools, and inspiration necessary to drive meaningful change within their communities and at a national level. This report serves as a foundational document, outlining the core concepts explored, the challenges identified, and the actionable strategies proposed to empower youth participation in these crucial areas.

Section 1: Setting the Stage – Understanding Climate Action in a Zimbabwean Context

The session on “Climate Action and Participatory Democracy,” facilitated by Natalie Gwatirisa, laid the groundwork by defining key terminology essential to comprehending the climate crisis. Participants delved into the distinctions between weather, climate, greenhouse gases, global warming, and sustainability. This foundational understanding underscored the pervasive nature of climate change and its far-reaching implications.

A critical historical perspective was introduced, tracing the origins of the climate crisis back to the Agrarian and Industrial Revolutions in Europe. The reliance on steam engines and coal during these periods propelled the Global North into advanced stages of development, while simultaneously initiating the extensive use of fossil fuels and the release of significant carbon emissions. A stark contrast was drawn between this historical trajectory and the current demands on the Global South to adopt renewable energy solutions, despite a severe lack of financial resources and the historical disadvantage of not being the primary polluters. This inherent inequity highlighted the political and complex nature of climate change, challenging the perception that it is solely a natural phenomenon.

The concept of “climate democracy” emerged as a central theme, emphasizing the critical need for climate issues to be prioritized by political parties and integrated into national agendas. It was acknowledged that addressing climate change is not an overnight task but requires persistent effort to embed the conversation within public discourse. The importance of decentralizing participatory democracy, especially during consultations and suggestions, was stressed, aiming to foster broader engagement and ownership of climate solutions.

A fundamental question posed during the session was: “Why are governments failing to address climate issues?” The ensuing discussion illuminated several critical factors:

- Prioritization of Economic Benefits: Fossil fuel industries and powerful individuals often prioritize short-term economic gains and profits over the long-term sustainability of the planet and the well-being of future generations.

- Lack of Climate Finance: The absence of dedicated climate policy or action without adequate climate finance was identified as a significant barrier. Developing nations, like Zimbabwe, lack the financial capacity to transition to renewable energy and implement robust climate adaptation strategies.

- Intersectional Interests in Negotiations: Global climate negotiations are often characterized by a “fight of words” (e.g., “should” versus “must”), with different nations and groups prioritizing their own intersecting interests rather than collaboratively addressing the real issues at hand.

- Limited Public Voice: The influence of powerful entities and their economic interests often overshadows the voices of the masses, particularly in countries where environmental degradation is linked to foreign investment, such as the Chinese extraction activities in Zimbabwe causing environmental crises.

The dire consequences of climate change were underscored, with research pointing to future water scarcity as a major threat, particularly impacting vulnerable populations in countries like Zimbabwe. The session also critically examined the nature of international aid, noting that donor countries often benefit from their involvement in recipient nations, necessitating a nuanced understanding of the “three Ps” that influence national contexts: Politics, Policy, and the PVO Bill, which is likely to affect climate democracy and youth engagement. The emergence of climate litigation as a tool for seeking justice against environmental damage was also introduced.

A crucial aspect of the discussion revolved around linking climate action to the immediate concerns of the Zimbabwean populace. It was recognized that ordinary citizens might perceive climate action as irrelevant when faced with pressing needs like electricity, jobs, and education. Therefore, student activists were encouraged to connect climate action with these immediate concerns, demonstrating how environmental degradation impacts education access, job opportunities, and daily living. The long-term consequences of climate change, such as widespread water scarcity affecting university students and communities, served as a powerful motivator for urgent action.

New Insights Gained (NEC Members):

- Climate Action is intrinsically linked to societal policies and influences every sector.

- The profound historical roots of climate change from the Industrial Revolution create global inequalities.

- The politicization of climate action, particularly the prioritization of profits over sustainability.

- The critical role of climate finance in enabling effective climate policy.

- The intersection of climate issues with everyday challenges like electricity, jobs, and education.

- The concept of “climate democracy” and the need to decentralize participatory processes.

Major Challenges/Threats Identified:

- Lack of public information and widespread misinformation about climate change.

- The political complexities and inherent conflicts between developed and developing nations regarding responsibility and finance.

- The prioritization of economic benefits by powerful groups over environmental sustainability.

- Systematic exclusion and low political will in climate advocacy.

- The perceived irrelevance of climate action to immediate societal needs.

Proposed Solutions and Actions:

- Combat Misinformation: Prioritize educating the citizenry on climate change, starting with general conversations, online engagement, and campus meetings. Well-informed individuals are more likely to take action.

- Integrate Climate Action into Policy-Making: Engage with policymakers at local and parliamentary levels to advocate for climate action. Encourage “Green Voting” by questioning government positions on climate in manifestos.

- Youth Participation: Enhance youth participation through mass education, advocating for compulsory climate knowledge modules in institutions, and engaging in debates and dialogues across provinces.

- Link Climate Action to Lived Realities: Emphasize the direct impact of climate change on students’ lives and communities (e.g., water scarcity, floods), making the issue tangible and urgent.

- Leverage Accountability: Use accountability as a tool to track leaders who shy away from climate action commitments. Participate in international forums to gain a broader understanding of global impacts.

Section 2: Building a Foundation – Governance (Accountability and Transparency)

The second session, facilitated by Ntandoyenkosi Dumani, delved into “Governance Issues on Accountability and Transparency,” providing critical tools for holding power to account. The session began by differentiating between embezzlement and misappropriation of funds. Embezzlement was defined as outright stealing, while misappropriationinvolves using money for purposes other than those intended, signifying mismanagement of funds. This distinction is crucial for assessing whether the Zimbabwean government is engaged in direct theft or simply mismanaging public resources, or both.

The overarching definition of corruption was established as the abuse of power or authority for personal gain over public good, emphasizing the critical element of power dynamics. Participants explored various types of corruption:

- Petty Corruption: Everyday, often unorganized corruption occurring between citizens and public officials, such as bribing a police officer.

- Grand Corruption: Organized and systemic corruption, often involving large-scale tenders and individuals with close ties to the ruling party, like the example of Wicknel Chivhayo, who allegedly receives tenders without delivering, leading to public suffering.

- Systemic Corruption: Corruption inherent within an institution or organization itself, where the entire system is designed to facilitate corrupt practices.

- Isolated Corruption: Instances where specific individuals within an institution are corrupt, rather than the institution as a whole.

The session then transitioned to defining good governance, characterized by “doing the right things and doing things right.” This involves adherence to laws, engaging with the people, and operating within established frameworks, which collectively grant legitimacy to the government. The concept of a social contract between citizens and those in power was introduced; a misalignment between their actions and public expectations signifies a breakdown of this contract. Good governance was further described as effective, efficient, and value-driven, advancing social justice in an accountable and transparent manner.

Social accountability was presented as a citizen-led aspect of good governance, empowering the public to hold power to account. This differs from parliamentary accountability, where ministries are held to account by legislative bodies. Social contracts, it was noted, are derived from existing policies and laws. The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) was highlighted as a critical tool, enabling citizens to access information held by government departments, a vital step in tackling corruption.

Key strategies for demanding accountability and transparency were outlined:

- Parliamentary Portfolio Committees: Utilizing these committees to scrutinize government actions.

- Transformative Change Making: A type of change that empowers people to act. This involves identifying natural allies(already supportive), fence-sitters (neutral but can be swayed), and spoilers (opposed). The strategy suggests investing more in fence-sitters

- Stakeholder Analysis, Power Mapping, and Risk Analysis: Essential tools for effective accountability demands.

- 198 Ways of Non-Violent Protest: A diverse range of tactics for peaceful advocacy.

Specific methods for holding leaders and institutions accountable were detailed:

- “Their Own Words”: Scrutinizing public promises and commitments made by leaders and institutions (e.g., party manifestos).

- “Their Own Reports”: Analyzing official reports (e.g., Auditor General Reports, Ministry reports) to identify discrepancies between promises and delivery.

- “Social Contracts”: Upholding the obligations of public institutions based on their social contract with citizens.

- “Their Own Tools”: Utilizing existing legal provisions and frameworks (e.g., Freedom of Information Act) that enable citizens to demand good governance.

- “Your Own Tools”: Employing citizen-led social accountability mechanisms such as budget tracking, social audits, community scorecards, and non-violent protests.

New Insights Gained (NEC Members):

- Corruption is deeply rooted in power imbalances and personal interests.

- The distinction between embezzlement and misappropriation.

- The different types of corruption: petty, grand, systemic, and isolated.

- The core principles of good governance and the social contract.

- The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) as a powerful tool for citizens.

- The importance of transformative change making, stakeholder analysis, and risk assessment.

- Specific methods for demanding accountability (using their words, reports, tools, and social contracts).

Major Challenges/Threats Identified:

- Pervasiveness of corruption (grand, petty, systemic).

- Lack of transparency and accountability from those in power.

- Citizen ignorance regarding specific laws and access to public information.

- Fear of seeking accountability due to repression and suppression.

Proposed Solutions and Actions:

- Building Transformative Alliances: Increase reach and influence by converting transactional allies into natural allies, focusing on winning over fence-sitters.

- Power Mapping and Risk Analysis: Strategically identify influential stakeholders and assess potential risks before taking action.

- Youth Conscientization: Educate youth on accountability tools and procedures, focusing on empowering them to access information (e.g., simplifying FOIA into local language pamphlets).

- Utilize Existing Reports and Policies: Follow up on government reports (Auditor General, Ministries) and parliamentary proceedings.

- Leverage Party Manifestos: Hold leaders accountable to their publicly stated commitments.

- Budget Tracking: Monitor government spending from local to national levels to ensure proper allocation and utilization of funds.

- Podcasting and Knowledge Sharing: Create platforms for continuous learning and dissemination of information on good governance and accountability.

- Overcome Fear: Emphasize that collective action builds power, starting with active allies and expanding to fence-sitters.

Section 3: Synergizing Action – Climate Action and Governance Intersections

The combined evaluation from the NEC members underscored the powerful synergy between climate action and good governance. The new insights gained highlighted the necessity of a strong information base for demanding accountability and transparency in governance, especially regarding climate-related information. This translates to an enlightened advocacy approach that is issue-based, community-aware, and strategically organized.

The major challenges identified in this integrated context pointed to systemic exclusion and limited participation in policy frameworks and implementation. The low attention and political will given to climate action due to competing economic priorities, coupled with deep-rooted corruption, were seen as significant threats, potentially leading to persecution for those who expose malpractices.

The NEC’s resolution to tackle “Governance issues on Accountability and Transparency” first was a strategic decision. The rationale is that rampant systemic corruption in the country and its institutions leads to misprioritization and misappropriation of resources. Addressing this will foster efficiency and effectiveness, though it requires strong will and commitment through activating communities to participate in awareness and advocacy.

Key Resolutions and Actions for Integrated Impact:

- Conscientization and Information Base: Start by educating communities from provinces to chapters, building an issue-centered information base.

- Grounding and Timeous Interaction: Engage youth in advocacy by being present where they are, informing them, and evoking their interests to enhance participation.

- Capacity Building and Training: Provide continuous training and capacity building to youth and student leaders, potentially through expert engagement.

- Information Centers and Resources: Establish platforms for rigorous dissemination of information to raise awareness and consciousness.

- Documentation and Archives: Record information and build archives for generational access and sustainability of knowledge.

- Online Campaigns and Networking: Utilize digital platforms for continuous advocacy and awareness, fostering broader engagement.

- Resilience and Continuous Engagement: Emphasize the values of resilience, being knowledgeable, and continuous advocacy in activism.

Section 4: Youth-Led Impact – Resolutions and Strategies for ZINASU

The training significantly inspired the ZINASU NEC members, evident in their high ratings of inspiration (average of 9-10 out of 10). The keywords describing the training – “Action,” “Research,” “Urgency,” “Transformative Change Making,” “Excellent,” “Informative,” “Issue-based,” “Polity,” “Policies,” “Sustainability,” “Enlightening,” and “Interesting” – reflect the profound impact of the sessions.

Specific Resolutions and Strategies for Youth Participation and Sustainability:

Enhancing Youth Participation:

- Mass Education: Implement widespread education on climate action, simplifying bureaucratic processes for decision-making.

- Climate Finance Advocacy: Advocate for immediate climate finance allocation in Zimbabwe, with transparent figures, and explore climate litigation lessons from other regional actors like Kenya.

- Freedom to Advocate: Demand a safe space for youth to discuss climate action without political persecution.

- Empowerment through Tools: Equip youth with tools to hold leaders accountable, ensuring they are informed about proposed policies and their implementation.

- Community Engagement: Foster grounded and timeous interaction with communities, integrating youth in advocacy and destroying social bridges that create seclusion.

- Strategic Engagement: Power mapping of stakeholders with influence and interest, focusing on converting transactional allies into natural allies.

Personal Activism Takeaways:

- Understanding Policies: Grasp government policies on renewable energy to influence actors with solutions.

- Leveraging Existing Reports: Utilize Ministry reports, Auditor General reports, and Parliamentary Portfolio Committee hearings to track corruption and promote good governance.

- Risk Analysis: Always calculate risks before taking action, especially in a repressive environment.

- Spectrum of Allies: Apply the concept of active, passive, and spoiler allies in personal activism.

- Strategic Communication: Emphasize effective communication for enhanced participation.

- “Their Own Words/Tools/Reports”: Prioritize using official statements and documents to hold power accountable before resorting to own tools.

Impactful Tools/Strategies for Youth Community:

- History and Lived Realities: Connect climate action to global history and current community experiences (e.g., Cyclone Idai, Gabon floods) to amplify urgency.

- Polity and Politics as Tools: Understand institutional structures and the political mood to navigate and pitch climate action effectively.

- Budget Tracking: Monitor budgets from local to national levels to ensure accountability and transparency in resource allocation.

- Manifesto Tracking: Use party manifestos as a basis for holding leaders accountable to their promises.

- Information Accessibility: Translate complex legislation like the Freedom of Information Act into easily digestible, local language pamphlets to empower grassroots citizens.

- Podcasting and Digital Platforms: Utilize modern communication tools to disseminate knowledge and engage a wider audience.

Sustainability of Knowledge Acquired:

- Compulsory Lectures/Modules: Advocate for mandatory climate knowledge in educational institutions.

- Provincial Debates/Dialogues: Organize ongoing discussions across provinces to deepen understanding and engagement.

- Green Infrastructure Projects: Initiate environmentally friendly projects within the organization, emphasizing participatory approaches.

- Opportunities for Global Engagement: Foster student participation in international climate discussions and programs.

- Knowledge Transfer: Ensure continuous knowledge transfer within student bodies and communities.

- Information Archives: Build and maintain accessible information resources for future generations.

- Continuous Advocacy and Awareness: Sustain efforts through online campaigns, networking, and expert engagement.

- Formulation of Information Material: Develop standardized templates for training others.

- Documentation: Systematically record all acquired knowledge and insights.